Mitochondrial gene therapy has a hand

October 09, 2018 Source: Chinese Journal of Science

Window._bd_share_config={ "common":{ "bdSnsKey":{ },"bdText":"","bdMini":"2","bdMiniList":false,"bdPic":"","bdStyle":" 0","bdSize":"16"},"share":{ }};with(document)0[(getElementsByTagName('head')[0]||body).appendChild(createElement('script')) .src='http://bdimg.share.baidu.com/static/api/js/share.js?v=89860593.js?cdnversion='+~(-new Date()/36e5)];

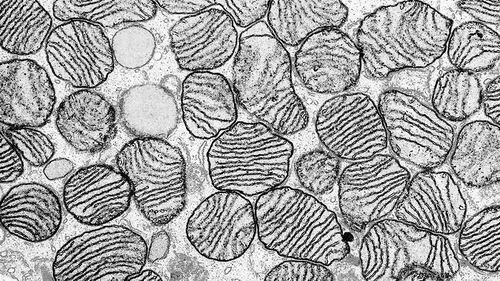

These mitochondria contain their own DNA, but they also carry mutations that cause disease. Image source: CNRI/SCIENCE SOURCE

The genome editor, known as a potentially revolutionary medical tool, is not a panacea. The organelle that supplies energy to cells - the mitochondria have its own mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), and mutations there can have devastating consequences including deafness, epilepsy, and muscle weakness.

Two studies published in Nature-Medical recently showed that two older genome editing tools can reduce the effects of mutations by reducing defective mtDNA in mice with mitochondrial disease. The evidence-based results of this principle have opened the way for the development of the first mitochondrial disease therapy. “These findings are extraordinary and even make it possible to conduct relevant trials in humans,†said Martin Picard, a mitochondrial biologist at Irving Medical Center, Columbia University, who was not involved in the above work.

However, turning these results into treatments will be very difficult. The genes encoding the genome editor must be introduced by the virus, and researchers have been struggling to make similar gene therapies work. Stephen Ekker, a molecular geneticist at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, who has no connection with the two studies, said, "The latest research can be verified in humans at any time." In fact, the two teams are already preparing for the start of clinical trials.

As a descendant of archaea that "settle" within early eukaryotic cells, mitochondria have their own small genome and a unique set of proteins that are not encoded by genes in the nucleus. Each cell can contain thousands of such organelles, and mutations in mtDNA can trigger a range of diseases. "If you combine all the mitochondrial diseases together, you will find them one of the most common causes of human genetic disease," said Michal Minczuk, a molecular biologist at the University of Cambridge, who led one of the research teams.

The controversial “three-parent baby†approach protects children from genetic mitochondrial disease. It involves replacing defective mitochondria in the mother's egg with the mitochondria of healthy donors. But the researchers did not find any treatment for patients with genetically incorrect mtDNA. “There are a lot of unmet needs at the moment,†Ekker said.

Cutting the mutant DNA can come in handy because the mitochondria destroy the cut molecules. More importantly, this potential therapy may not eliminate all defective mtDNA in countless mitochondria. Carlos Moraes, a mitochondrial biologist at the University of Miami's Miller School of Medicine, said that mtDNA copies carried by parents with mitochondrial disease may or may not have harmful mutations, and that the proportion of the two mutations must reach a certain level before symptoms appear. . “If you can reduce this ratio below the threshold, clinical performance may disappear.â€

However, CRISPR is not an option. It relies on RNA strands to direct the DNA-cutting proteins to the correct position in the genome, and most researchers suspect that mitochondria can occupy these guide RNAs. To this end, the two teams dialed the clock back to the pre-CRISPR era and tested two other editing methods - zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs). Both methods include DNA cleavage proteins designed to direct target tracking DNA without the presence of a guide RNA. Although these systems are more cumbersome and less versatile than CRISPR, they can also cut DNA at specific locations.

Two groups of researchers used a similar virus that was considered harmless to deliver the gene responsible for editing the DNA protein into the cells of the mutant mouse. In this strain, some mtDNA copies produce mutations in a gene encoding a transfer ribonucleic acid (tRNA) that aids in the assembly of mitochondrial proteins. This tRNA is less in mutant mice than normal mice, although they only show mild cardiac abnormalities.

Moraes and colleague Sandra Bacman and his team members injected the virus containing the TALENs gene into the leg muscles on the right side of each mouse. As a control, they injected the virus lacking the TALENs gene into the same muscle on the left side. Six months later, the number of mutant mitochondrial DNA was reduced by more than half in muscles injected with the TALENs gene, while a reduced ratio of damaged DNA to normal DNA usually produced a 50:50 threshold for symptoms.

Minczuk and postdoctoral Payam Gammage and colleagues designed equivalent ZFNs and injected the virus carrying them into the tail vein of mice. Once in the bloodstream, the virus will travel through the heart that also contains defective mtDNA. When scientists analyzed the heart tissue of these animals after 65 days, they found that the proportion of mutant mitochondrial DNA was reduced by about 40%.

Because minor cardiac abnormalities are difficult to document, researchers used molecular markers to measure the success of the therapy. Both teams determined that tRNA scarce in mutant mice proliferated after gene therapy. Minczuk's team also measured several metabolic molecules that showed better mitochondrial performance in mice.

The researchers believe that in order to apply this strategy to humans, they have to ensure that the genes for TALENs and ZFNs reach the right tissues in the right amount. In any case, Moraes said he and his colleagues are trying to organize a safety trial for their method in patients with mtDNA mutations. This will begin as early as next year. Minczuk said his team also hopes to start clinical trials, but there is no timetable. (Zong Hua)

Related paper information: DOI:10.1126/science.aav5152

Chinese Journal of Science and Technology (2018-10-09 3rd Edition International)

Medical Equipment Disposal,Syringes Needles Sizes,Disposable Syringe,Insulin Syringe

FOSHAN PHARMA CO., LTD. , https://www.fspharmaapi.com